Porc

Porc

A la nostra cultura, el porc (Sus scrofa) és un animal tan saborosament volgut com menyspreat. La segona definició que figura al diccionari n´és un avís: “persona bruta físicament o moralment”. D´entrada, doncs, el porc no ho té gens planer: el llenguatge el castiga. Expressions com “menges com un porc”, “vas brut com un porc”, “aquesta habitació sembla una cort de porcs”, fan que el porc no tingui gens fàcil treure´s de sobre aquesta llàntia, o millor llosa. Un altre exemple de la seva desconsideració resa com segueix: “Al porc, si li treuen la brutícia es mor”.

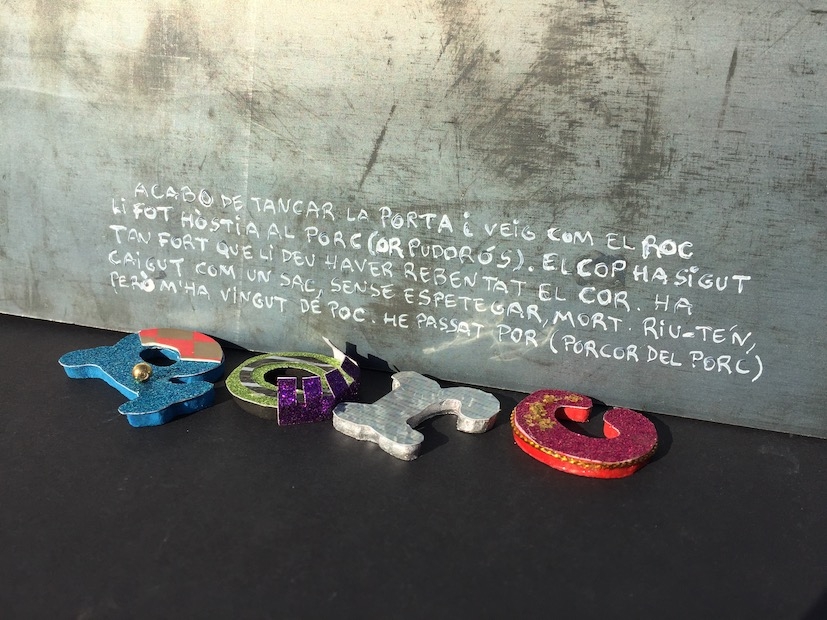

Només he fet que començar. El porc també l´associem amb el greix, i això tampoc li fa cap favor. Diem d´un home que “sembla un bacó”, o d´una dona que “és una verra”. Si avui estar gras, tenir molt greix, es considera un demèrit insà, a mitjans dels anys cinquanta ser panxut i rodó era entès com un senyal virtuós i inequívoc de no passar gana. Tot un ventall de refranys i frases fetes repiquen sense descans i l´acaben de retratar. Així doncs, el porc és brut per naturalesa perquè li agrada rebolcar-se a la merda, i llardós perquè només pensa a menjar, “menjar i beure, vida de porc”; i s´ho fot tot corrents i de pressa, “el que sobra de menjar que ho aprofitin els porcs”, a més a més amb mala bava, “el pitjor porc o el més roí, sempre menja la millor gla”. Compte perquè si bades et pot rosegar les sabates i si no vigiles se´t menjarà el peu, “el dimoni té cara de porc”. El porc també és ordinari, “de porc i de senyor se n´ha de venir de mena”, fa massa xivarri i té el destí assegurat, només faltaria, “a cada porc li arriba el seu Sant Martí”. És un pinxo, “el porc diu orellut a l´ase”, i arriba a ser més que dolent, gairebé traïdor, “el porc mossega fins després de mort”. I alerta que va de debò! Els animals humans hem d´estar sempre amatents perquè no ens encomani, amb nocturnitat i traïdoria, una perillosa malaltia (zoonosi), la Triquinosi, la qual ens pot dur fins a les portes de la mort després d´un bon àpat. A mi que tant m´agraden les galtes de porc amb el greix ben torradet!

Ja veus, una bona peça aquest el porc! Però té el que es mereix, que no s´enganyi, “val més ser gos tota la vida que porc un any”, etziba el refrany. Tampoc és estrany, doncs, que contra aquest animal tan mesquí no estiguem sols, que d´altres cultures també hi participin, “dir-ne més mal que Mahoma del porc”. Sí, jueus i musulmans el consideren impur i n´han prohibit el consum de la seva carn. Vaja, entre “pitus i flautes”, els animals humans només fem que “dir-li el nom del porc”.

Amb tot aquest “acarnissament”, un animal d´aquesta mena, només pot ser bo per menjar. Això fa que “del porc se n´aprofita tot” —un conegut refrany castellà diu que “del cerdo me gustan hasta los andares”—, des de les potes, morro i orelles fins al fetge, ronyó, cor, pulmons, passant pels budells o els testicles; i de la seva carn podem gaudir d´una gran varietat de productes i derivats: pernil, botifarra, xoriço, llom, mortadel·la, paté, salsitxes, sobrassades... Què s´ha cregut! I posats a aprofitar lícitament, el porc també és un model de referència per a la investigació biomèdica, en àrees com la Farmacologia, la Cirurgia (tècniques quirúrgiques, trasplantaments), model en malalties infeccioses, cardiovasculars, degeneratives, i tot un munt d´altres activitats —si s´han de fer línies genètiques de porcs nans per abaratir costos d´estabulació, manteniment i disseny experimental, entendràs que calgui fer-ho—. Crida al cel, sí, crida l’altruisme d´aquest animal que fa tanta pudor, la veritat. —A més, pensa que de retruc també se´n beneficien gossos, ratolins... i primats no humans, poca broma—. Sí, tornem a les dites —per què serà que el porc n´acumula tantes?—: “Un porc mai mor de vell”.

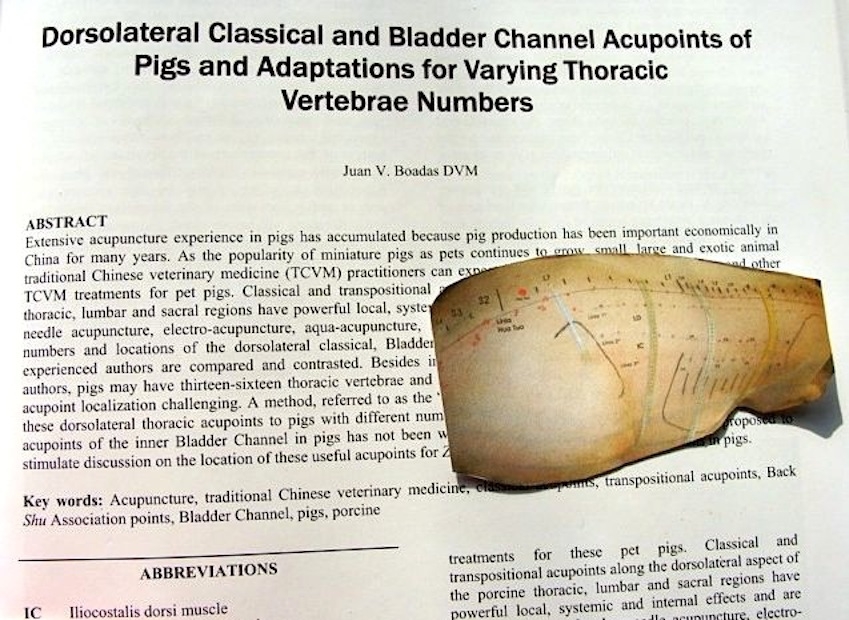

A la cultura tradicional xinesa —els xinesos també el troben bo. Històricament, la medicina veterinària tradicional xinesa ha acumulat una gran experiència en el tractament d´algunes de les seves malalties amb l´acupuntura i les herbes—, el porc i el seu germà el senglar són considerats animals Yang (força, moviment, rapidesa), associats a la fertilitat i la virilitat. És un de les dotze bèsties que apareix en el zodíac xinès i, a la teoria dels cinc elements, es relaciona amb l´element Aigua on també hi és, com a òrgan de gran importància, el Ronyó. El porc, doncs, també és per ells un animal “de vida”.

I ben segur que ho és. Creu-me, si mai has entrat dins d´una cort de porcs amb ganes d´estar-t´hi una bona estona i t´has assegut a terra en un racó sense ganes d´emprenyar, o t´has fet amb alguna truja engabiada, ho hauràs notat. El porc és molt viu, espavilat, tafaner, expressiu —cridaner com pocs, s’esvalota només per un gest—, sol tenir un caràcter molt sensible —un cop et coneix, es desfà perquè no deixis de palpar-lo— i si el tractes prou, observaràs que té una gran capacitat d´aprenentatge.

Però d´aquestes qualitats els animals humans no en mengem, i amb la tan nostra natural tendència de mirar cap a un altre cantó i endolcir la vida —només faltaria, prous penes hi ha al món per entretenir-se amb un porc! sentiràs a dir— gaudim creant entelèquies, digues-li “Babe, ¡el cerdito valiente!” que aprèn a fer de gos pastor i ens parla, i raona, i ens arriba a emocionar, i ens entreté els nens i les nenes, pobret. Una delícia de porquet en minúscula que badalla, balla i té sentiments! És com el meu germanet, només que és un porquet. No l´has vist com dorm? Deliciós: això ens apropa als animalons i amb dues passes més ja som a la natura!

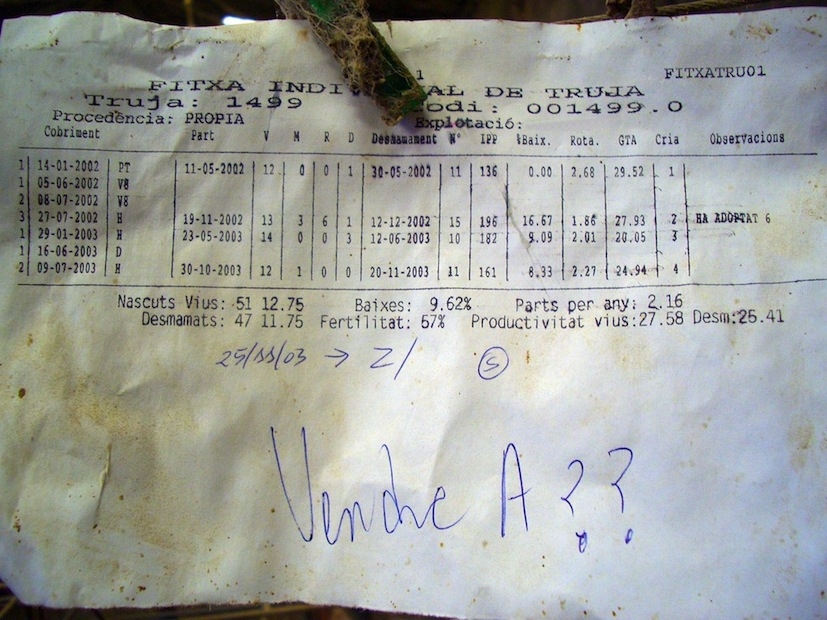

On també es podrien fer pel·lícules és a les granges de producció intensiva. Un bon càmera comunicaria intenses emocions, però no estic segur que tinguessin gaire audiència, la veritat. Aquí, el porc s´engreixa per estossinar (granges d´engreix), i alhora també se´l cria per proveir a les primeres (granges de mares). I és una sort, diuen, que els aspectes relacionats amb el benestar animal cada dia vagin tenint major importància, si més no la que els comptes d´explotació permetin. Només dir-vos que avui poden penjar-se mòbils del sostre d´una cort a fi i efecte que el porc o la porca jugui amb ells, es fomentin les activitats d´exploració i així no s´estressi tant. Tot això també és beneficiós. Tot un detall.

Sí, pinzellades del nostre porc. El porc. Un porc. Porc. I ho continuarà sent. Sent una paraula sense noms i cognoms. Males cartes. Mala flaira pels animals humans, oi? Acabo com he començat, amb una perla, un refrany que tot i no ser gaire conegut, no deixa de ser inquietant: “si vols veure el teu cos, mata un porc”.

Pig

In contemporary culture, the common pig (Sus scrofa) is desired and despised in equal measure. According to the dictionary, the second definition of a pig is “a physically or morally unclean person”. The creature doesn’t have it easy — even everyday language is against it. There are all manner of sayings and expressions that put the animal in a bad light: “Eating like a pig”, “Dirty as a pig”, “This room looks like a pigsty”, or even “Happy as a pig in shit”.

And that’s just for starters. The pig is also associated with fat, which doesn’t really do it any favours — calling someone a pig can be a rather unkind way of referring to their excess weight or their less-than-ideal physical appearance. It’s interesting to remember that although nowadays being overweight is frowned upon (being as it is associated with being unhealthy), just sixty years ago the opposite was true: it was seen as a clear sign of being well-fed and thus denoted a certain level of wealth. The humble pig is tirelessly defined and portrayed in a whole range of common sayings: the pig is filthy by nature because it loves rolling around in the mud (“He ain't fittin' to roll with a pig”); it’s fat because it’s always thinking about food (“To pig out”); it eats carelessly and sloppily (“To make a pig of oneself”). Sadly, it’s also known for its meanness and devious behaviour — when you’re not paying attention, it might well try and bite at your feet (“The devil has a pig’s face”). The pig is also seen as a loser, a lowlife, a traitor (“A pig bites even after death”); and when we least expect it, it may even infect us with trichinosis… Yet most of us would not turn our nose up at the sight of some juicy grilled pork chops! Certainly a colourful character then, our piggy. But don’t be fooled — it gets what it deserves (“It’s better to be a dog for a lifetime than a pig for a year”). We shouldn’t be suprised, then, that other cultures have similar views to ours. Jews and Muslims, for example, consider the pig to be an impure animal and prohibit pork consumption.

Given all this bad reputation, the pig is best left for cooking. In fact, pretty much the entire body of a pig can be eaten: “I love every part of a pig — even its walk”, as the well-known Spanish saying goes. Legs, snout, ears, liver, kidneys, heart, lungs, guts and testicles. Not to mention all the derivatives: ham, sausages, fillets, mortadella, paté, etc. And while we’re at it, let’s not forget the many uses of swine as models in biomedical research, pharmacology, surgery (surgical treatments and transplants), infectious, cardiovascular and degenerative diseases, and a whole host of other activities — even the genetic production of dwarf pigs to lower the costs of stabling, maintenance and experimental design. Suddenly the humble animal, “squealing like a pig”, fat and filthy, now seems almost selfless, giving itself up to all sorts of experimentation while other animals such as dogs, mice and non-human primates enjoy their freedom (“A pig never dies of old age”).

According to Chinese tradition — traditional Chinese veterinary medicine, through herbs and acupuncture, has long been effective in the treatment of certain swine diseases — the pig and the boar are considered Yang animals (strength, movement, speed) and are associated with fertility and virility. It is one of the twelve animals that make up the Chinese zodiac and, through the five elements theory, is related to Water and to the element Kidney as a vital organ. It seems then that for the Chinese population, the pig is very much an animal representing life.

And so it should be. Those of you who have visited a pigsty and have found themselves wanting to sit in a corner and quietly watch the animals play will agree with me. The pig is undoubtedly a lively creature, smart, gossipy and expressive. It’s excitable, attention-seeking and ever-so-sensitive: once it gets to know you, it’ll do anything to make you keep petting it. And if you stick around long enough in its company, you’ll also notice its great capacity for learning.

Of course, we cannot live off its endearing qualities alone; besides, we have quite enough to worry about in the world without wasting time messing around with pigs! So we make do with the next best thing, “Babe, the Gallant Pig” — a sheep-pig who can talk, reason, move us to tears and even entertain our little ones. A yawning, dancing, adorable little piggy, with feelings too! Just like my baby brother in fact. Haven’t you seen it sleeping? Unbearably cute — and what a way to get closer to nature.

Something else we could make movies about is intensive animal farming. I’m sure a good director would be able to weave a highly emotional tale, but I fear it wouldn’t see much of an audience. Here, the pig is bred to be fattened for slaughter. It’s a good thing animal welfare is growing in importance around the world, at least as much as the exploitation industry will allow. Nowadays pigsties even carry mobiles hanging from the roof for the pigs to play with and thus lower their stress levels. How generous.

So there you have it, the humble pig in a few broad brushstrokes. The pig. A pig. Pig. Forever a pig, no name nor surname. Rotten luck. For him and, perhaps, for us too, don’t you think? I’ll end as I began, with another saying, perhaps not quite as well-known but no less disturbing: “If you want to see your own body, kill a pig”.